Most modern languages are written from left to right, thus we assume that thinking from left to right is the most natural way to process information expressed with these languages. This is particularly true for Large Language Models (LLMs) which are typically trained to predict the next word in a sequence, known as left-to-right (L2R) language models. But what if, for certain tasks, thinking backward could actually be better?

A recent paper from Apple researchers, titled "Reversal Blessing: Thinking Backward May Outpace Thinking Forward in Multi-choice Questions", explores a counterintuitive approach to data augmentation: training LLMs on "reversed" sequences. It delves into the potential of right-to-left (R2L) language models, and their effectiveness in tackling some tasks such as multiple-choice questions (MCQs). The paper can be found here, and the supporting code can be found in the GitHub repository here. In this blog post, we are going to explore some of the key ideas and findings from this paper.

Medium post can be found here.

Left‐to‐right (L2R) Autoregressive Factorization

Most LLMs are trained to predict text in a strictly left‐to‐right order. Left-to-right autoregressive (L2R) factorization is the fundamental mathematical principle underlying how these models generate text, based on decomposing the probability of a sequence into a chain of conditional probabilities.

The Theory

Given a sequence of tokens \(x = (x_1, x_2, \dots, x_T)\), the model expresses the joint probability as a product of conditional probabilities:

where \(x_{<t}\) represents the preceding tokens \((x_{1}, x_{2}, \dots, x_{t-1})\). This approach can introduce inductive biases and approximation errors that compound at each step, which may not be optimal for all tasks.

For training, models typically optimize the log-likelihood of the sequence for numerical stability and easier differentiation:

Right‐to‐left (R2L) Autoregressive Factorization

R2L factorization is the mathematical mirror image of L2R, where each token is conditioned on the tokens that come after it.

The Theory

The joint probability is factored in the reverse order

where \(x_t\) is the sequence of subsequent tokens \((x_{t+1},\dots,x_T)\). To train an R2L model, each training instance is tokenized, and then the order of all tokens is reversed before being fed to the model. Although L2R and R2L factorizations represent the same distribution in theory, their neural network approximations learn different behaviors and exhibit different performance characteristics.

Key Questions

The paper investigates the following three questions:

- How to evaluate R2L models on knowledge extraction and basic reasoning tasks?

- Can R2L factorization match or surpass L2R’s capabilities in knowledge extraction and reasoning for downstream tasks?

- What are underlying factors determining the preference of L2R or R2L factorizations?

Multiple‐Choice Questions

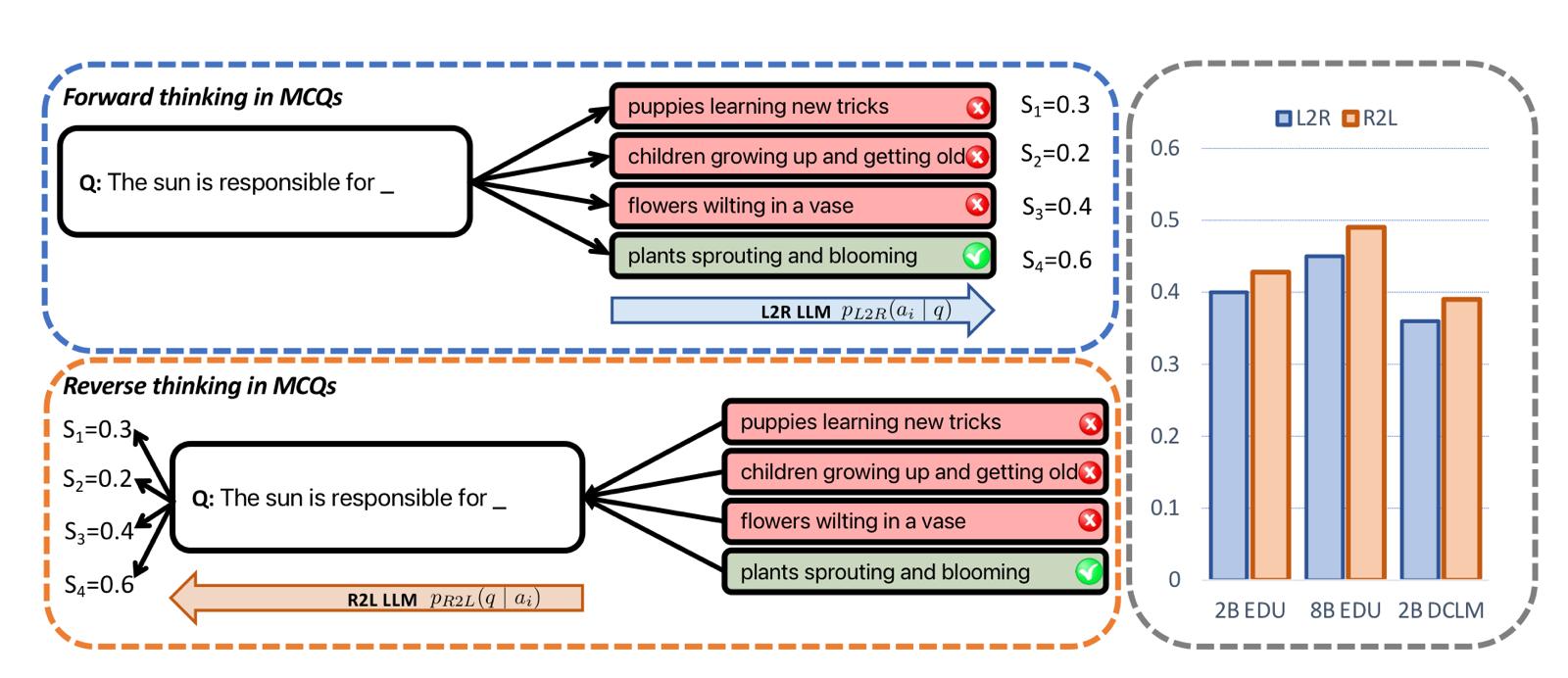

Multiple‐choice questions (MCQs) are a common benchmark for evaluating an LLM’s knowledge, reasoning, and calibration. As we can see in Figure 1, in their simplest form, an MCQ comprises:

- A question \(q\)

- A set of \(n\) candidate answers \(a_1, \dots, a_n\)

- Exactly one correct answer \(a^{*}\) among these \(n\) choices

The paper uses MCQs as the primary testbed for comparing the two reasoning directions.

L2R on MCQs

Let \(q\) be a question with answer candidates \(\{a_1, a_2, \dots, a_n\}\). L2R models compute a score for each answer \(a_i\) given the question \(q\). This score is typically the log-probability of the answer, normalized by its length \(N_i\) to prevent bias towards shorter answers

The model then selects the answer with the highest score. This approach, however, can suffer from "surface-form competition," where semantically similar answers (e.g., “dog” vs. “puppy”) split the probability mass, penalizing the correct answer concept.

R2L on MCQs

For R2L models, the paper proposes "reverse thinking" based on Bayes' rule, which evaluates how likely the question is given a particular answer. The authors test three scoring paradigms and find that the simplest one performs the best:

- Paradigm 1 (Normalized + Prior):

- Paradigm 2 (Unnormalized + Prior):

- Paradigm 3 (Unnormalized, Uniform Prior):

Empirically, Paradigm 3 consistently yields the highest MCQ accuracy. By ignoring the prior probability of the answer, it avoids noisy estimations and cleanly sidesteps the surface-form competition issue.

Why Does Reverse Thinking Work? The "3C" Hypotheses

The paper explores three main hypotheses for why one direction might outperform the other: Calibration, Computability, and Conditional Entropy.

Calibration and Surface‐Form Competition

Reverse thinking (Paradigm 3) fixes the calibration issue because it evaluates \(p(q \mid a_i)\). Since the question \(q\) is the same for all choices, there's no competition among different answer forms. This allows the model to fairly assess how well each distinct answer concept explains the question, effectively auto-normalizing the choices.

Computability: Forward vs. Reverse Task Difficulty

This idea draws an analogy to tasks like prime factorization, where the forward operation (multiplication) is easy and the reverse (factoring) is hard. Similarly, some reasoning tasks might be intrinsically easier to compute in one direction. However, the paper notes that most MCQs are "shallow" tasks involving pattern matching rather than deep symbolic inversion, making this a less dominant factor.

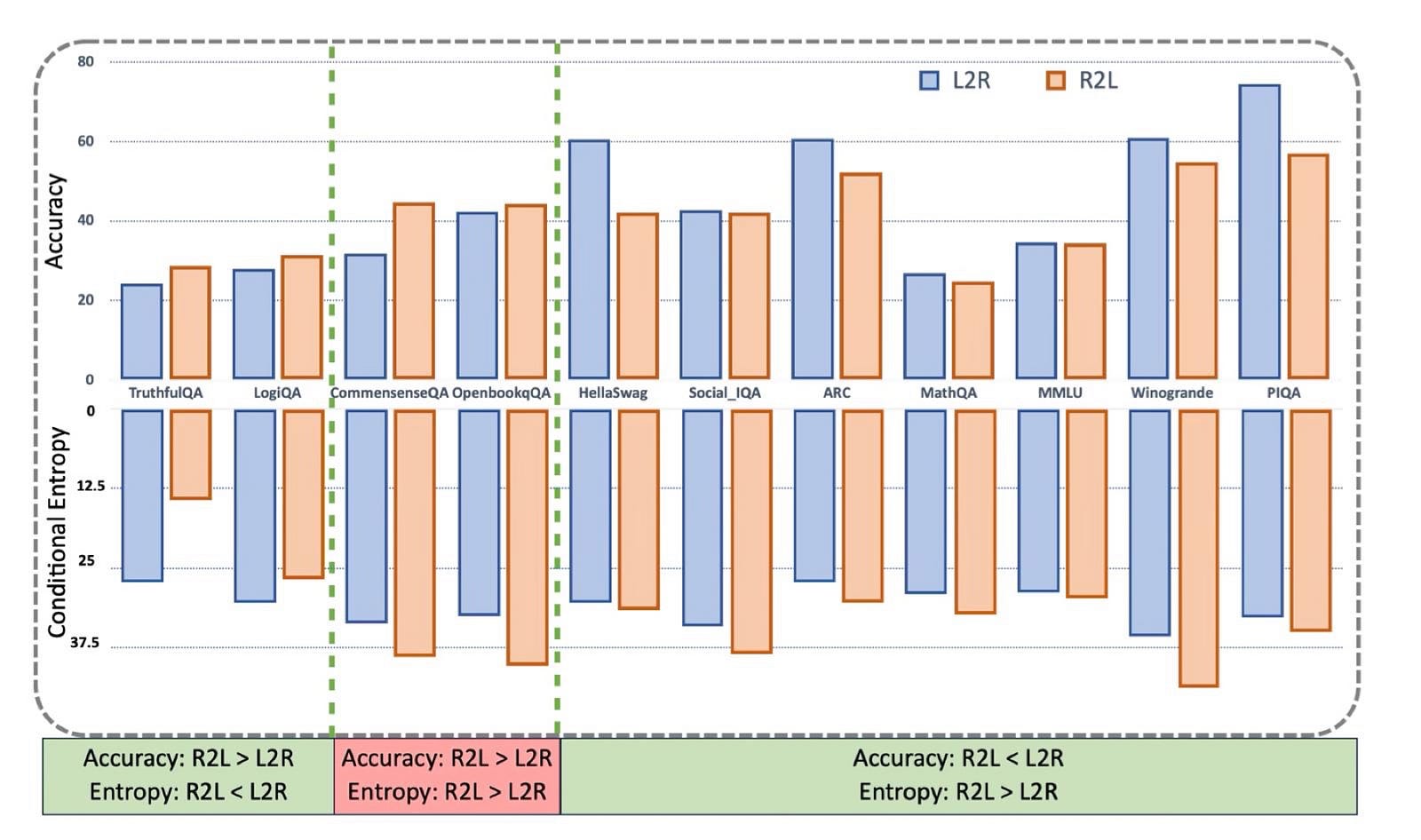

Conditional Entropy

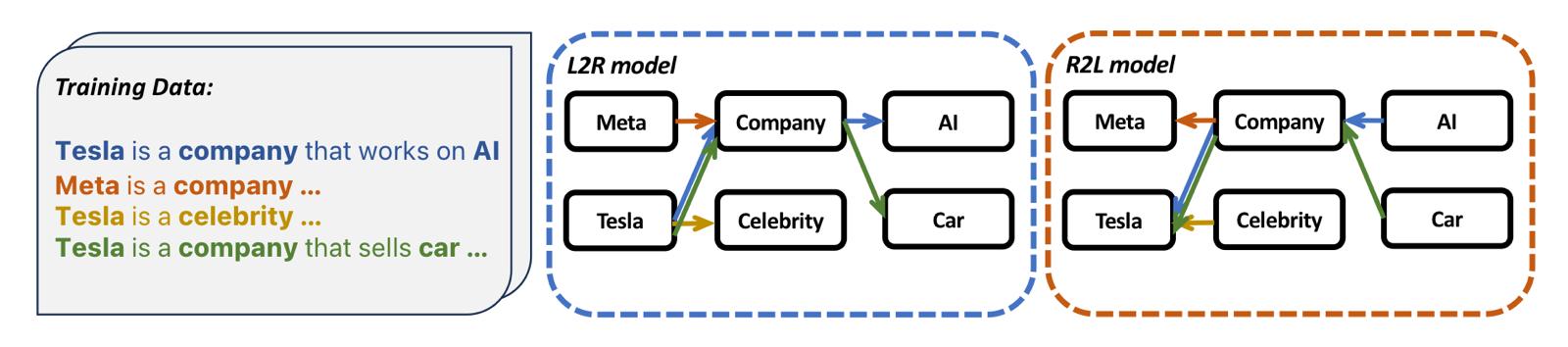

This is proposed as the most unified and powerful criterion. The core idea is that the direction of reasoning with lower conditional entropy is inherently less uncertain and thus easier for a model to learn accurately.

An LLM can be viewed as constructing a directed search graph (a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)) from the training data, mapping between information entities. An L2R model and an R2L model trained on the same data will form analogous DAGs but with opposite edge directions, as illustrated below.

The efficiency of searching these graphs in either direction is what conditional entropy aims to measure.

- L2R Conditional Entropy \(H(A∣Q)\): Measures the average uncertainty over answers given a question.

- R2L Conditional Entropy \(H(Q∣A)\): Measures the average uncertainty over questions given an answer.

The paper hypothesizes that the direction with the minimum entropy will yield higher accuracy. Since directly computing these entropies is intractable, the authors estimate them using a Monte Carlo proxy based on single-sample "rollouts" from the models. The results show a strong correlation: the direction with lower estimated conditional entropy typically achieves higher accuracy on the benchmark.

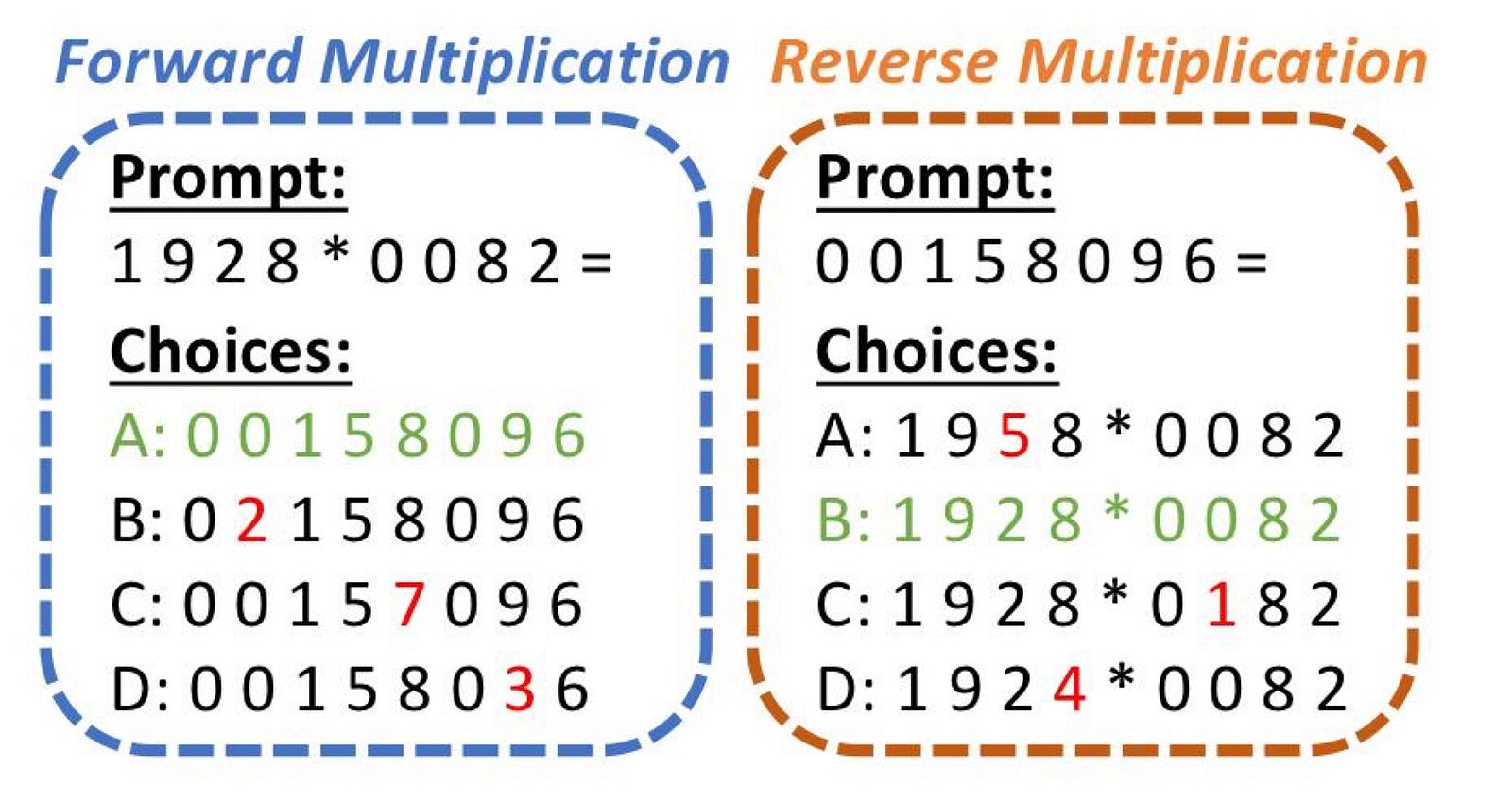

Controlled Simulation: 4‐Digit Multiplication

To isolate the "3C" effects, the researchers designed a controlled experiment using 4-digit multiplication.

- Forward X (Multiplication): The task is \(m \times n = p\). This is a deterministic, many-to-one mapping with a theoretical conditional entropy of \(0\).

- Reverse X (Factorization): The task is \(p = m \times n\). This is a one-to-many mapping with a higher theoretical conditional entropy of \(1.49\) nats.

The results were definitive:

- In Forward X, the L2R model (aligned with the zero-entropy direction) achieved \(99.81\%\) accuracy, while the R2L model struggled.

- In Reverse X, the R2L model (now aligned with the zero-entropy direction) achieved \(100\%\) accuracy, far surpassing the L2R model.

This experiment provides clear evidence that conditional entropy is a key determinant of performance when other factors are controlled.

Synthesis and Implications

Why Conditional Entropy Dominates

Across both real-world MCQ benchmarks and the controlled arithmetic simulation, conditional entropy emerges as the primary predictor of whether L2R or R2L "thinking" yields higher accuracy. A lower entropy signifies a more deterministic mapping from condition to target, making the learning task easier and the resulting model more accurate. For example, on tasks like TruthfulQA, the mapping from a true statement (answer) back to a question about it is likely less ambiguous than predicting one of many possible true statements from a question, hence R2L's advantage.

Calibration and Computability as Secondary Factors

While entropy is the main driver, calibration and computability are important secondary factors that can explain outliers or amplify performance differences. For example, on CommonsenseQA, R2L performs better even though the entropy difference isn't as pronounced. This is likely because the task is rife with paraphrased and semantically similar answer choices, a scenario where R2L's ability to mitigate "surface-form competition" provides a decisive edge.

Conclusion

“Reversal Blessing” demonstrates that thinking backward can indeed outpace forward thinking on specific MCQ tasks. By systematically comparing L2R and R2L models, the authors show that conditional entropy is the principal driver of which factorization is preferred.

Key Takeaways:

- Reverse thinking sidesteps calibration issues like surface-form competition, making it ideal for tasks with synonymous answers.

- Conditional entropy offers a practical criterion to decide between L2R and R2L, with the lower-entropy direction generally being superior.

- The best reasoning direction is task-dependent, and a one-size-fits-all approach may be suboptimal.

Ultimately, this work invites us to rethink the default L2R pretraining paradigm. By embracing the potential for bidirectional reasoning and choosing a factorization direction based on task-specific entropy profiles, future LLMs could achieve more robust, calibrated, and efficient performance across a broader array of problem domains.